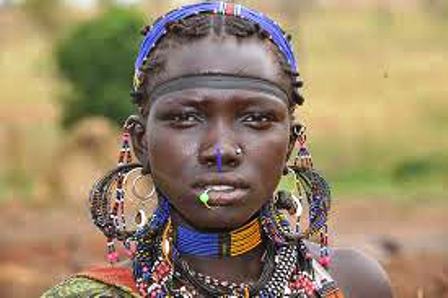

Ik people and their Culture in Uganda

Who are the Ik People in Uganda? The Ik (sometimes called Teuso, though this term is explicitly derogatory) are an ethnic group numbering about 10,000 people living in the mountains of northeastern Uganda near the border with Kenya, next to the more populous Karamojong and Turkana peoples.

The Ik were displaced from their land to create a national park and consequently suffered extreme famine.

Also, their weakness relative to other tribes meant they were regularly raided. The Ik are subsistence farmers who grind their own grain.

The Ik language is a member of the highly divergent Kuliak subgroup of Nilo-Saharan languages.

Community structure of the Ik People

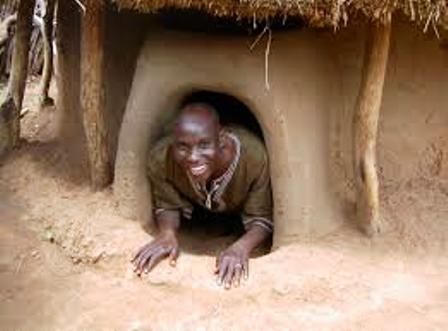

The Ik people live in several small villages arranged in clusters, which comprise the total "community".

Each small village is surrounded by an outer wall, then sectioned off into familial (or friend-based) "neighborhoods" called Odoks, each surrounded by a wall.

Each Odokis sectioned into walled-off households called asaks, with front yards (for lack of a better term) and in some cases, granaries.

Culture of the Ik of the Karamajong

the kids from ik karamajong

the kids from ik karamajongChildren by age three are at least sometimes permanently expelled from the household and form groups called age-bands consisting of those within the same age group.

The 'Junior Group' consists of children from the ages of three to eight and the 'Senior Group' consists of those between eight and thirteen.

No adults look after the children, who teach each other the basics of survival. However, it is not certain whether this practice is typical Ik tradition or merely triggered by unusual famine conditions.

Tainter proposes this fragmentation to be an artifact of the dire circumstances where each person must depend on their own resources alone to find food and the age peers band together primarily to protect themselves from older stronger children who would take their food. He also argues that the present social fragmentation is the result of extreme deprivation on a more complex and functional culture, an argument also made

Whilst carrying out research for this article I asked several Ugandans about their experiences of the Ik people in the northeast of the country. Not one of those that I asked knew to which people I was referring.

Today only a small number of the Ik remain, living perched on the top of the Rift Valley Escarpment on the border with Kenya and Sudan, 420 kilometres northeast of Kampala in the District of Kotido.

The Ik originated from a larger group of Kuliak-speaking people that came either from Ethiopia or from as far north as Egypt.

On their way south they divided into three groups: the So, the Nyang’I and the Ik.

The Ik literally means ‘head’, and the people are so-called because they believe they were at the head of the migration and the first of the Kuliak to reach Uganda

On arrival in this part of East Africa, the Ik roamed freely across the borders of Sudan, Kenya and Uganda, hunting and foraging in the Kidepo Valley.

Flanked to the west by the large and technologically superior Dodoth Karimojong, and to the east by the Kenyan people, the Turkana, over time the Ik have been forced further and further into the mountains.

The Dodoth Karimojong and Turkana are both cattle-herders who steadily muscled the Ik away from the more fertile plains up into the hills. Above the plains, self production was made difficult by steep mountain conditions and, more recently, severe drought,

Both of which tax their foraging methods. In contrast to both of lifestyle of hunter-gatherers, capturing game from the Kidepo Valley and growing only a few crops to supplement their diet.

The Karamajong refer to the Ik by the derogatory term of ‘Teuso,’ literally meaning ‘poor people of dogs, without cattle or guns.’

The Karamajong refer to the Ik by the derogatory term of ‘Teuso,’ literally meaning ‘poor people of dogs, without cattle or guns.’However, during the 1960s, Milton Obote declared the area a Ugandan National Park, meaning the expulsion of the Ik and a halt to their hunting way of life lifestyle of hunter-gatherers, capturing game from the Kidepo Valley and growing only a few crops to supplement their diet.

However, during the 1960s, Milton Obote declared the area a Ugandan National Park, meaning the expulsion of the Ik and a halt to their hunting way of life.

Adding to the Ik’s worries of drought and a lack of game as they were forced from a hunter-gathering mode of living into one based on crop production, the Ik became caught between the mutual cattle raids carried out by the Turkana and Dodoth peoples.

‘When the cattle raiders pass through they normally attack us’ explains one of the parish chiefs, referring to the widespread habit of looting and burning Ik villages whenever the opportunity arises. Both herder groups now refer to the Ik by the derogatory term of ‘Teuso,’ literally meaning ‘poor people of dogs, without cattle or guns.’

Today the diminishing Ik are around 5,000 in number and face the daily struggles of insecurity, hunger and lack of water. These problems are compounded by having little political representation to help them struggle out of this situation.

The Turkana are a regular menace in terms of raids, raping and killing members of the Ik, coming across the border from Kenya to do so. The Dodoth also dabble in similar atrocities. The Ik are also caught in the middle of the two groups’ attacks on one another, being accused of not warning one of the other’s presence.

One such situation leads to another, larger problem: namely, a lack of food. The Ik do not keep livestock due to fear of it being taken from them. They have resorted to other methods but a constant fear of being shot whilst going out to collect food or water remains - especially when they have to leave their own community to travel to a far away borehole..

Even once Ik women have covered excessive distances down from the mountains to reach a borehole, they are then forced by armed Dodoth groups (every cattle herder carries a gun) to wait in line until all others have finished. That is to say the cattle, the men, the children and finally the Dodoth women must drink before the Ik can take their turn.

On a political front, the Ik’s perceived insignificance as cultivators compared to the represented needs of their pastoral neighbours makes changing the situation almost impossible. Governed by Dodoth, the sub county office in Kalapata does not represent the Ik in a neutral light and the district office at Kotido does not even cast its eye over Ik inhabited territory.

Language is also a problem for this oppressed people. They speak Icetot which is a Nilotic language. Although it takes much of its vocabulary from neighbouring Nilotic speaking tribes, Icetot is not understood or spoken in the surrounding areas, thus accentuating the existing physical isolation of the Ik.

Even when members of the Ik journeyed to Kampala for political ends, they were unable to understand what was being said or the substance of possible solutions. Anything that was discussed was manipulated by the Dodoth representatives for their own benefit, whilst Ik leaders were left in the dark.

As a people, the Ik seem to epitomise a population that has been forgotten by its own government.

Their isolated existence means they have just two primary schools and have only recently built a medical clinic that relieves them of a 30km trek to the hospital.

Diseases such as cholera and malaria dealt a heavy blow to the Ik population during the 1980s, such was the inaccessibility of medical care. A social worker describes the Ik as ‘a real case of deprivation and social injustice’ and explains that ‘no single social facility has ever been erected in the area by the authorities…’

It comes as no surprise that only 4 people amongst the Ik have ever been to secondary school and even doing so has not secured them a job.

In contrast to Colin Turnbull’s view in his book The Mountain People (1972),

in order for the Ik to survive as a people we must take a sympathetic stance and seek highly plausible methods for their progress in the future. As Richard Hoffman has incessantly pointed out, it is not too late for the Ik.

Unfortunately the major anthropological work on the Ik by Turnbull has painted a highly unfavourable picture of these people and even recommends dispersing them throughout other areas of Uganda.

The Mountain People is a much criticized, and rightly so, account of the Ik that should only be seen as intended to support socio-biological thinking of the time: that man in its raw state is nothing but selfish and governed by animalistic drives. Turnbull finds fault with the Ik people in their transition from hunter gathering to a lifestyle that requires self production.

He describes a people who used to share everything according to the hunter-gatherer code, as one where men now eat hunted food far from the village whilst women collect only for themselves. He sees the Ik in a negative light, for whom ‘honesty has become foolishness and lying an art form,’ in the quest for survival.

What Turnbull took to represent the ‘inherent evil’ of the Ik can only be seen as features of the starvation, trepidation and suspicion that their climate, neighbours and governors have left them helpless against.

Turnbull seeks to link the Ik experience of change with psychobiological arguments based on man’s independent will to survive. He does not take into account the luxury of structures such as language, laws and cooperation that other societies undergoing change had at their disposal to help maintain social norms.

Rather than seeing negative behaviour, those that have known the Ik over an extended period of time only report their fondness for one another, family or friends, and their wholehearted desire to preserve their language and culture in the face of adversity.

Though desperate, the plight of the Ik is in no way a lost cause. Commentators believe that, with some much needed understanding from the outside world, the Ik can survive.

Progress has already been made on many fronts. For example, government troops from the Ugandan People’s Defence Force have been employed in Kamion to guard against raids from the Turkana tribe.

This has increased accessibility to food and water and eased the tension within the region. Involving representatives from the Ik on the political spectrum, particularly bringing them to Kampala, demonstrates hugely encouraging steps on the path of progress.

Listening to their previously ignored voice clears high barriers; now it is just a matter of employing a translator who can accurately represent the Ik without the fear of Dodoth retaliation.

The United Nations World Food Programme is also tuned into the starved needs of the Ik. Unfortunately there have been incidences where lorry loads of supplies are halted by Dodoth people at Kalapata on the pretence that the roads are too bad to continue.

The food is then left in their hands, leaving the far needier Ik unaided. This is a problem with obvious solutions, so food aid should no longer be too far from the Ik’s grasp.

Political wrangling between President Museveni and his Kenyan counter-part, Kibaki, to stop cross-border raiding, has moved up the government’s agenda of improving security for the Ik and other so-affected groups.

There are even reports of members of the Dodoth Karimojong themselves starting to take a much more sympathetic view towards the Ik and helping them in their quest for safety from the raids.

In a similar vein, neighbouring Ugandans have helped the Ik increase agricultural productivity by assisting them in developing methods appropriate to their new environment.

Of course little can be done to change the torrid environment or reinstate old hunter-gatherer methods in their current conditions, but with people around, the Ik working together and a sympathetic ear from the rest of Uganda, the future may yet be a whole lot brighter for the Ik.

Other Related Pages

Kenya Cultural Origins | Kenya Student Rules | Kikuyu People | Luo in Kenya | Masai People | Samburu People | Student Class Rules | Turkana People in Kenya |

Recent Articles

-

Garam Masala Appetizers ,How to Make Garam Masala,Kenya Cuisines

Sep 21, 14 03:38 PM

Garam Masala Appetizers are originally Indian food but of recent, many Kenyans use it. Therefore, on this site, we will guide you on how to make it easily. -

The Details of the Baruuli-Banyara People and their Culture in Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:32 AM

The Baruuli-Banyala are a people of Central Uganda who generally live near the Nile River-Lake Kyoga basin. -

Guide to Nubi People and their Culture in Kenya and Uganda

Sep 03, 14 12:24 AM

The Nubians consist of seven non-Arab Muslim tribes which originated in the Nubia region, an area between Aswan in southern

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.